I’ve unfortunately had a fair few run ins with the medical sector in India since 2023, and that has naturally made me curious about how it operates, especially from the point of view of decarbonisation (also, for anyone who is curious, the operation theatre I was operated upon in looked more like an enormous store room than what they look like in Grey’s Anatomy). Here’s what I found out.

The Sector

The healthcare sector is a sprawl of the multiple interacting industries, and includes healthcare providers (hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, physiotherapy), medical equipment & supplies (devices, diagnostic machines, consumables), pharmaceuticals & biotechnology (drug/vaccine makers, gene therapy, diagnostics), health IT & digital health (electronic records, telemedicine, AI platforms), managed Care/insurance (public/private health insurers, billing services), medical research & education (clinical trials, medical/nursing colleges, consulting), and ancillary/ wellness industries (medical tourism, public health, waste disposal). There’s also sectoral overlap with the real estate sector for the buildings these services are performed, or equipment manufacture at, supply chain and logistics, food and nutrition, and marketing.

So that’s a lot.

Global Statistics

All these industries accounted for approximately 10% of worldwide GDP- translating to nearly $10 trillion in health spending annually.1 At the moment, the sector is the 5th largest emitter in the world, making for between 4.4% (2019) and 5.2% of total global greenhouse gas emissions currently12, and might reach 6 gigatons by 2050 without aggressive decarbonisation efforts.1 To help put this into perspective, 6 gigatons are 6,000,000,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO₂). A typical passenger vehicle emits about 4.6 metric tons of CO₂3 per year, so the sector may emit as much as 1.3 billion passenger cars by 2050- and there are currently between 1.23 to 1.47 billion passenger cars in operation worldwide.45

Before we go into the energy use, let’s understand how the emission break ups are categorised (Emissions are organised into three “scopes” to make it easier to identify where pollution comes from and how to address it): Scope 1 emissions are those emitted directly by the activities performed by the emitter, for example, the gas burned in your hospital’s boilers, emissions from ambulances and owned vehicles, or fumes from certain medical gases; Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions related to the electricity, steam, heating, or cooling you purchase from someone else (like a utility company)- the pollution from this type of usage is created at the point of energy generation; and Scope 3 emissions are those not covered in the previous two, but are still only produced to be used in the healthcare sector- this makes it the trickiest and also the largest part of all the emissions from the sector- it includes the entire supply chain- so, for example, if a hospital buys a surgical kit, Scope 3 includes the emissions from making, packaging, and delivering it.

So now onto the break ups: globally these industries used 17% for Scope 1 emissions, 12% for Scope 2, and the remaining (71%) for Scope 3 uses in 2019.2

The India Story

The Indian healthcare sector made up 3.3% of national GDP as of 2022 (USD 80 per capita7), with expectations of this rising to 5% by 2030.6 India’s GDP in 2022 was approximately $3.35 trillion USD.89 India’s total GHG emissions in 2022 were about 217.9 million metric tons CO₂ equivalent.10 3.3% of National GHG Emissions (if scaled directly from GDP share) would be 217.9 million tonnes multiplied by 3.3%, or 217.9 multiplied by 0.033, which is approximately 7.19 million metric tons CO₂ equivalent (1,563,000 passenger cars). Actual sectoral emissions may vary depending on emissions intensity (a measure of how much energy is used to produce a unit of economic output). The Indian healthcare sector is estimated to account for about 2%11 of national GHG emissions (4.36 million metric tons ÷ 4.6 ≈ 948,000 passenger cars), but if we scale strictly by GDP share (because there are no confirmed numbers), this figure is about 7.2 million metric tons CO₂e for 2022. I’ve also taken it as an equivalent percentage of GDP rather than the reported numbers because the Indian healthcare sector was estimated to emit 2% of India’s total GHG emissions in 20192, but between 2019 and 2022, the Indian healthcare sector grew by 17.5% annually12, significantly outpacing the growth of the economy as a whole between these years89. The healthcare sector’s 17+% CAGR versus the broader economy’s 7–8% CAGR means healthcare’s portion of the economy (and its GHG emissions footprint) increased during these years, likely easily outstripping the 2% estimate for 2019.

Decarbonisation Pathways

Why Is Healthcare So Carbon-Intensive? Because it uses a lot of energy, equipment, and material, many of which are:

- Single-use: For sterility and safety, everything from syringes to gowns and often surgical tools are single-use. Single-use medical devices and consumables can account for up to 86% of the total carbon footprint of a hospital surgery, driven mostly by the production and use of such disposable items.14

- Resource intensive: Hospitals need round-the-clock, energy-guzzling HVAC, lighting, emergency backup power, and sterilisation.2

- Dependent on imports: Many hospitals, especially in countries like India, depend on imported medical technology, devices, and pharmaceuticals. The carbon footprint of these goods includes not just their production but also packaging, long-haul transport, and storage, increasing the indirect (Scope 3) emissions portion of healthcare’s footprint.15

- Hazardous waste products: (e.g., sharps, blood-stained items, infectious waste) along with general plastic and food waste. Treatment and safe disposal—often via incineration—consumes a lot of energy and may itself release greenhouse gases and toxic substances such as dioxins and furans.16

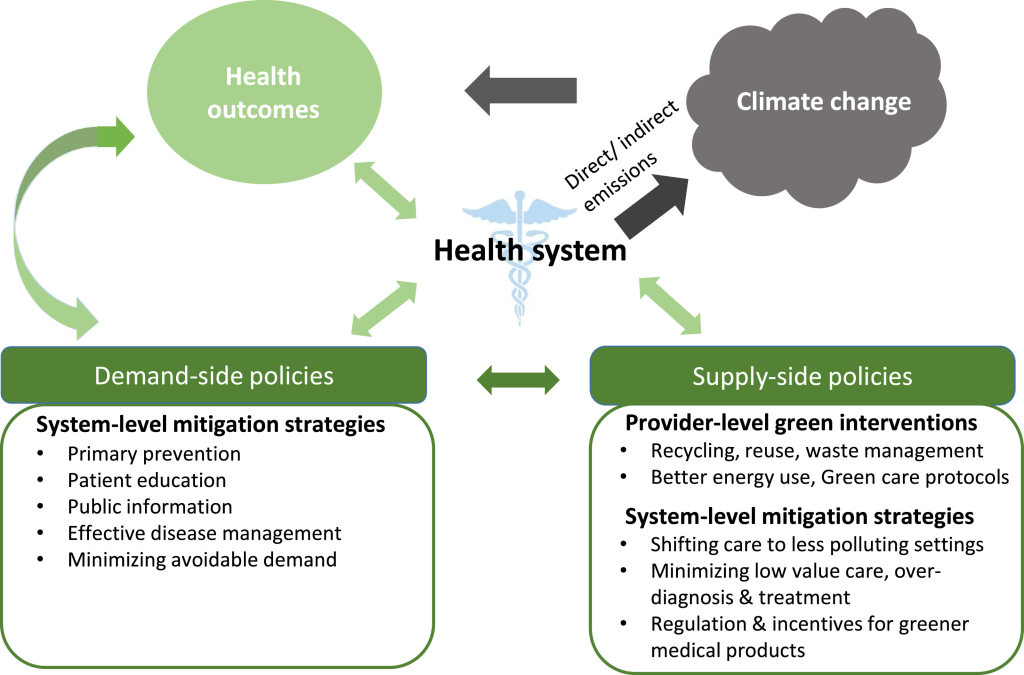

A number of general and specialised strategies can be used to decarbonise operations in the healthcare sector.

General strategies (common to all energy users):

- Transition to Renewable Energy: Switching to solar, wind, hydroelectric, and even geothermal sources for electricity, dramatically cutting GHG emissions. On-site solar photovoltaic (PV) installations, especially in hospitals, are reducing operational costs and increasing resilience.

- Onsite energy generation: While not quire fully operational, or even fully sustainable yet, non renewable energy generation such as cogeneration or trigeneration, are certainly better than grid electricity usage as they will reduce transmission and distribution losses, and further the waste heat can be used to generate both heating and cooling, or both, for the premises.

- Energy Efficiency Improvements: Upgrading and retrofitting buildings with energy-efficient lighting, HVAC (heating, ventilation, air conditioning), chillers, star-rated equipment, and insulation cuts down consumption by 30–50% in some cases. Use of variable frequency drives (VFDs)17, intelligent sensors, and IoT-based monitoring allows real-time optimization.

- Green Building Design and Retrofitting: Buildings that follow green building codes and energy conservation codes consume fewer resources, while existing facilities can be retrofitted with modern energy management systems and green technologies.

- Decarbonizing Supply Chains: Emphasis on green procurement, sustainable sourcing, and responsible supplier engagement ensures that scope 3 emissions are reduced and managed on an continuously.

- Waste Management and Reduction: Sustainable waste handling, recycling, and waste-to-energy programs decrease landfill emissions and support circular economy practices.

- Renewable or Low-GWP Refrigerants: A shift to low global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants to meet emerging regulations and climate commitments. (Global Warming Potential (GWP) is a measure of how much a greenhouse gas traps heat in the atmosphere compared to the same amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) over a specific time period, usually 100 years.18) Moving to refrigerants with GWPs far below 700 can cut emissions from these systems by as much as 78% (relative to older HFCs).19

Healthcare-specific strategies:

- Low-carbon pharmaceuticals: Pharmaceuticals are among the highest-emitting components of healthcare’s carbon footprint, often due to energy-intensive manufacturing, complex supply chains, and waste at the point of use. A McKinsey study found that adopting green-chemistry principles to redesign synthetic processes and use recyclable solvents could cut pharmaceutical active ingredient (API) manufacturing emissions by up to 30%.20

- Reducing Low-Value Care: Avoiding unnecessary admissions, surgeries, and tests not only saves resources but reduces both direct (hospital-based) and indirect (supply-chain) emissions. Evidence-based guidelines to minimize unwarranted care can have substantial savings.21

- Telemedicine and home- based care: Shifting care (where safe and appropriate) from hospitals to home or community settings lowers the need for energy-intensive infrastructure. For instance, remote physiotherapy after surgery demonstrated fewer rehospitalizations and better outcomes at lower environmental cost.21

- Digistisation of care: Telehealth cut CO₂ emissions associated with cancer care by over 80% at one major U.S. center. Another 2023 multi-state analysis found telehealth averted 21.4–47.6 million kg of CO₂ per month—equivalent to keeping up to 130,000 cars off the road every month.22

- Treatments: Anaesthetic gases (like desflurane and nitrous oxide) have very high GWPs and alternatives (total intravenous or regional/local anesthesia) can be used where clinically appropriate without compromising treatment outcomes and patient health.23

The healthcare sector is a vital, vibrant part of our world. It’s complexities and interdependencies make it difficult to decarbonise, not least that each decision should be made keeping patient service in mind, and at first it looks like decarbonisation does the opposite. Yet, we also know that climate change is making people sick: heatwaves, floods, wildfires, and storms are becoming more frequent and severe, and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 2030 and 2050, climate change will cause roughly 250,000 additional deaths per year from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress alone- in some regions, heat-related deaths among people over 65 have risen by 70% in two decades24; vector-borne diseases (like malaria, dengue, and Zika) are spreading to new areas as rising temperatures and altered rainfall enable disease-carrying insects to thrive in new regions and seasons, and water- and food- borne illnesses become more common when heavy rains, floods, or droughts contaminate water sources or affect food supply chains25; rising air pollution including smog and higher particulate matter in the air we breathe smog and particulates), increases rates of asthma, chronic lung conditions, and cardiovascular disease affecting children, people with chronic illnesses, and urban residents are especially vulnerable; crop failures contribute to malnutrition and stunting2425; extreme events, displacement, and ecosystem loss contribute to greater rates of anxiety, depression, PTSD, and other mental health disruptions26; rising seas, severe storms, and food/water shortages also force people from their homes, increasing displacement, conflict, and health emergencies- often overwhelming local health systems and worsening inequities24… and working on sectoral decarbonisation will help those same people the sector works to protect.

Sources

- Five Fast Facts on Healthcare’s Climate Footprint

- Healthcare’s Climate Footprint – How the global health sector contributes to the global climate crisis and opportunities for action – Health Care Without Harm (Climate-smart health care series) Produced in collaboration with Arup, September 2019

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle

- Number of Cars in the World? Actual Answer

- Number of Cars in the World 2025: Key Stats & Figures

- India’s healthcare expenditure expected to surge from 3.3% to 5% of its GDP by 2030: CareEdge

- India’s Healthcare Expenditure Expected to Surge from 3.3% to 5% of its GDP by 2030 – CareEdge

- India GDP Macrotrends

- India: Gross domestic product (GDP) in current prices from 1987 to 2030(in billion U.S. dollars) – Statista

- India Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Tonnes of CO2 Equivalent per Year: Fuel Exploitation

- The healthcare sector needs to lead the way on decarbonisation – Asian Hospital and Healthcare Management

- Indian Healthcare Market projected to reach $638 billion by 2025: Bajaj Finserv AMC

- Decarbonizing the Health Care System

- Experts address single-use plastics in healthcare – University of Edinburgh

- Why India is poised to become a global hub for MedTech manufacturing

- Healthcare Waste—A Serious Problem for Global Health

- What is a VFD?

- The Future of Refrigeration: Low-GWP Refrigerants

- Innovating for Impact: Next Generation Refrigerants for a Sustainable Tomorrow

- Decarbonizing API manufacturing: Unpacking the cost and regulatory requirements

- Getting Started: Low carbon clinical care in hospitals

- Evidence that telehealth cuts carbon emissions grows

- Green health: how to decarbonise global healthcare systems

- Climate change – World Health Organisation

- Health and Climate Change – World Bank

- Climate change and health – Better Health