NB: Ishan made me do this.

Why did Ishan Kishan come out swinging at 6/2 chasing 209 instead of playing it safe? Why did Pat Cummins bowl first in the 2023 World Cup final despite everyone expecting him to bat? Why did Harmanpreet Kaur throw the ball to part-time bowler Shafali Verma in the 2025 Women’s World Cup final when India desperately needed wickets?

These aren’t random decisions. They follow patterns that psychologists and economists have studied for decades. Three frameworks help us understand these three cricket choices:

- Expected Utility Theory – How perfectly rational people should make decisions (decision making for robots)

- Prospect Theory – How people actually make decisions when facing risk, or when they feel like they are winning or losing

- Behavioral Economics – The mental shortcuts and biases that affect our choices

Expected Utility Theory1

Expected Utility Theory assumes people make decisions by calculating the average outcome of their choices. They think about the all the possible outcomes, try to understand how likely each outcome is, and how much they would like or dislike it if any of these outcomes happened. Then pick the option where this calculation works out best.

Expected Utility Theory assumes three things:

- People can calculate probabilities accurately

- They will pick the option with the best average outcome

- They make decisions based on pure logic, not emotions

This theory is useful because it gives us a standard for what “rational” decision-making looks like. It’s like the baseline or the “correct answer” against which we can compare real human behavior.

But here’s the problem: people don’t actually follow this framework, because we are not always rational beings.

Prospect Theory2

Developed by Nobel Prize-winning psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky,3 Prospect Theory says that people behave in predictable but “irrational” ways. The central insight of the theory is that Losses hurt about twice as much as equivalent gains feel good,4 and that outcomes are evaluated based on the current position of the person evaluating them- not on absolute values of satisfaction.

Here are two examples:

Scenario 1: Gain Frame

- Option A: You’re guaranteed to get $450

- Option B: Flip a coin—50% chance you get $1,000, 50% chance you get nothing

Expected Utility Theory says: Both options have the same expected value ($500- the value you would get on average if the coin is flipped many times), so you should be indifferent.

But Prospect Theory predicts: Most people choose Option A (the guaranteed $450). Why? Because the certainty of a gain feels good, even if it’s smaller.

Scenario 2: Loss Frame

- Option A: You’re guaranteed to lose $450

- Option B: Flip a coin—50% chance you lose $1,000, 50% chance you lose nothing

Expected Utility Theory says: Both have the same average loss, so again you should be indifferent.

But Prospect Theory predicts: Most people choose Option B (the coin flip). Why? Because they’ll take a gamble to avoid a certain loss. The possibility of losing nothing appeals to them.

Behavioral Economics5

While Expected Utility Theory focuses on rationality and Prospect Theory focuses on how we evaluate gains vs. losses, Behavioral Economics is the broader field studying all the ways our brains take shortcuts that lead us astray. It’s the study of cognitive biases.

Here are some key behavioral biases:6

- Anchoring Bias: We get too attached to the first piece of information we hear, even if it’s wrong or irrelevant.

- Status Quo Bias: We prefer to keep things as they are, even if alternatives are better (“We’ve Always Done It This Way”).

- Confirmation Bias: We seek out information that confirms what we already believe, and ignore contradictory evidence.

- Availability heuristic: Overweighting recent memorable incidents while discounting regular events. A heuristic is a mental short cut, like a rule of thumb. For example, my dad just wears whatever my mom takes out for him to wear. If he has to make a decision, his heuristic is to wear whatever is at the top of the pile of clothes in his cupboard.

- Recency Bias: We overweight recent events when making decisions, ignoring longer-term patterns.

- Sunk Cost Bias: We make decisions based on money we’ve already spent, even though that money is gone and shouldn’t affect future decisions.

These biases often work together to distort decisions:

- Anchoring + Confirmation bias = You anchor on an initial belief, then only see evidence confirming it

- Recency bias + Availability heuristic = Recent vivid events feel more common than they are

- Status quo bias + Sunk cost bias = You stick with current choices because of what you’ve already invested, even if better alternatives exist

Kishan7

Now back to cricket. Ishan Kishan walked in and launched an all-out assault—76 runs off just 32 balls at a strike rate of 237.5. He reached his fifty in 21 balls, the fastest by any Indian against New Zealand. Together with Suryakumar Yadav, he added 122 runs in just 49 balls. India won with 28 balls remaining.

Captain Suryakumar later said: “I’ve never seen anyone bat at 6/2 in that manner and still end the powerplay around 67 or 70”.8

From a pure Expected Utility perspective, when chasing very high totals in T20 cricket, the mathematics often favor immediate aggression because conservative batting creates an impossible required run rate in later overs.9 Studies using dynamic programming and, more recently, advanced machine learning techniques to analyse Twenty20 (T20) cricket suggest that, when facing high targets, chasing teams are often more successful when they adopt an aggressive approach from the beginning, which inherently requires accepting elevated risk.10

In Prospect Theory terms:

- Reference point: The current losing position (6/2, massive target)

- Frame: Loss domain (already behind, likely heading toward defeat)

- Predicted behavior: Risk-seeking to escape the loss domain

Research on sports shows11 that athletes in trailing positions consistently take more risks: higher shot volumes in basketball, more aggressive substitutions in football, elevated foul rates. Trailing teams recognise that maintaining the status quo (playing safe) guarantees defeat, so they escalate risk dramatically.

Kishan’s aggressive batting aligns perfectly with Prospect Theory’s prediction: when facing almost certain defeat through conventional cricket, players become willing to take massive risks for a chance at victory. The post-match quote captures this psychology: “I asked myself, can I do it again? I had a very clear answer”.8 This suggests Kishan mentally framed the situation as an opportunity (a chance to produce something extraordinary) rather than a threat (protecting his wicket).

The partnership transformed what looked like a losing position into a comfortable victory. India reached the target with 28 balls to spare. Kishan’s risk-seeking behavior in a loss frame achieved precisely what conservative cricket might not have done—a pathway to victory from an apparently losing position.

Cummins12

In the 2023 CWC final, Pat Cummins won the toss and chose to field. Conventional wisdom… indeed old Australian wisdom certainly suggested batting first and setting a target,13 but against an unbeaten India playing at home, his instincts were unfortunately proven correct (Cummins admitted he was “unsure right until the toss”14).

Cummins articulated this logic: “Not getting it right with the bat first would be fatal in a way not doing so with the ball wouldn’t”.14 This is sophisticated risk assessment—recognising that different choices carry different consequences even if probabilities are similar. Besides, research on toss decisions shows that in modern ODI cricket, there’s no consistent advantage to batting first.15 The decision was called “one of the bravest in Australian sport history”, because if it failed, criticism would be merciless.16 The “safe” choice (bat first) protects reputation even if suboptimal. Cummins accepted the reputational risk to make what he calculated as the statistically better decision. Rare leadership.

Abhishek Sharma, India’s incandescent T20 opener later spoke with his IPL team mate Travis Head to understand Head’s mindset during Australia’s chase. Abhishek says Head told him, “when I asked him about his mindset in the World Cup, he told me that we only had the batter’s meeting. And in the batter’s meeting, we only thought about how to make 400 today”.17

Now think from an Indian batter’s perspective. The pressure of playing a home world cup final in front of thousands of fans vociferously supporting your team… I would have thought it would let them express themselves openly, but the opposite happened.

Why did the pressure of a home World Cup final constrain Indian batters instead of liberating them? The answer might sit at the intersection of Prospect Theory, loss aversion, and reputational risk.

Prospect Theory tells us that people in a gain frame become risk-averse. After winning every match before the final and spreading true joy through the nation, every wicket that fell in the final may have felt like a loss from a guaranteed future, not a normal match event. Loss aversion might have kicked in hard here: the pain of being the one who throws it away may have felt far greater than the joy of being the hero. This is textbook loss aversion: the psychological weight of potential failure exceeded the psychological reward of potential glory.

So Indian batters subconsciously optimised for:

- Minimising blame

- Preserving wickets

- Maintaining respectability

Not maximising runs.

Contrast this with Ishan Kishan whacking the skin off the cricket ball earlier this week… the contrast is clear, isn’t it? Note here that Kishan had earlier been dropped and treated poorly by the BCCI after making a double hundred,18 plus he had failed in the previous match. He still backed himself and chose the (objectively) riskiest option.

Elite cricket decisions are clearly less about skill or courage and more about how players psychologically locate themselves on the gain–loss spectrum. In all three moments—Kishan’s assault, Cummins’ toss call, and India’s batting freeze—the decisive factor wasn’t talent or tactics, but where each decision-maker placed their psychological reference point. None of these decisions become correct because they succeeded or failed. They become understandable because the theory predicts them before the outcome is known. Human beings behave differently under different frames—and elite sport amplifies those tendencies.

Kaur

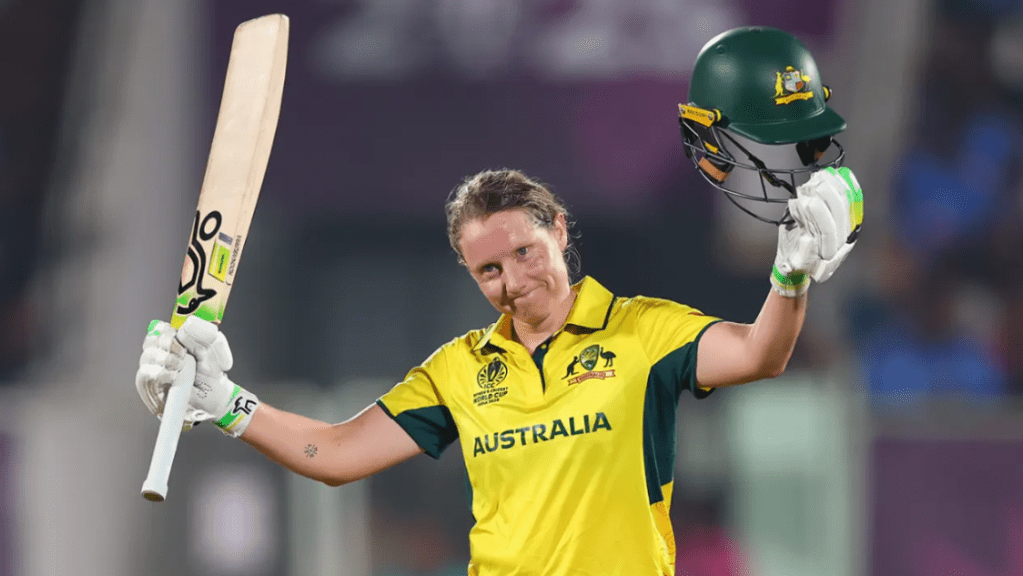

And now to something joyful. Remember when Harmanpreet Kaur threw the ball in the final to Shafali Verma?19 Me too! Shafali is a specialist batter who had bowled only 14 overs in 30 ODIs with just 1 wicket.20 Shafali took 2 wickets in her first over (Sune Luus caught and bowled, Marizanne Kapp).19

From a rational Expected Utility perspective, Harmanpreet’s decision seems questionable. Pure EUT would favour specialist bowlers with known probabilities and track records over using an untested part-timer who could get whacked for a 30 run over on a bad day. But Shafali was having a good day, and Harman trusted that. Shafali’s ongoing frame of mind was of confidence. and Prospect Theory says people evaluate their options based on their current position. Shafali also represented an unexpected variation that South African batters hadn’t prepared for.

Harman successfully overcame several behavioural biases to toss the ball to Shafali that night:

- Status Quo Bias Overcome: The “safe” choice was continuing with regular bowlers—what teams typically do. Harman broke this pattern. Research shows captains typically exhibit strong status quo bias, especially in high-pressure situations. Harman went against this natural tendency.

- Sunk Cost Fallacy Avoided: Teams often persist with established bowlers because they’re “supposed to be” the specialists—they’ve been selected for this role, practiced extensively, etc. Harman didn’t fall into this trap. The fact that Shafali wasn’t a specialist shouldn’t matter if the situation calls for something different.

- Availability Heuristic Countered: The most “available” option mentally was the regular bowlers—they’re the specialists, they’ve bowled throughout the match. But Harman looked beyond the obvious choice.

She later explained, “When Laura and Sune were batting, they were looking really good, and I just saw Shafali standing there. The way she was batting today, I knew today’s her day. She was doing something special today, and I just thought I have to go with my gut feeling”.20 This represents what researchers call “recognition-primed decision making”—experienced decision-makers recognising patterns and trusting intuition developed through years of experience.21 MS Dhoni’s captaincy showed similar intuitive leaps: giving the last over to Joginder Sharma in the 2007 T20 World Cup final, promoting himself ahead of Yuvraj in 2011.22 Neither Kaur nor MS South African captain Laura Wolvaardt later admitted: “Shafali’s bowling was the surprise factor, frustrating that we didn’t expect it”.23

In all,

- Ishan was risk-seeking because he perceived himself in a loss frame.

- Indian batters became risk-averse because they perceived themselves in a gain frame.

- Cummins accepted reputational risk to avoid catastrophic match risk.

- Harman overrode status quo bias by compressing experience into instinct.

Ultimately, none of these choices were brave because they succeeded; they were brave because they resisted the gravitational pull of risk aversion, reputation, and habit. Under pressure, cricket strips decision-making down to its psychological core: how afraid are you? Elite sport doesn’t reward those who merely minimise mistakes. It rewards those who understand when the cost of caution is greater than the cost of failure — and who are willing to act accordingly. The moments we celebrate are not triumphs of bravery so much as triumphs over instinct—reminders that greatness often lives in decisions that feel unsafe.

Sources

- Expected Utility – Definition, Calculation, Examples (Corporate Finance Institute)

- The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2002 – Press Release (NobelPrize.org)

- Prospect Theory (The Decision Lab)

- Prospect Theory in Psychology: Loss Aversion Bias (Simply Psychology)

- Prospect Theory Overview & Examples (Statistics By Jim)

- 5 Everyday Examples of Behavioral Economics (The Chicago School)

- Anchoring Bias (The Decision Lab)

- The Sunk Cost Fallacy (The Decision Lab)

- IND vs NZ 2nd T20 2026: India ride on Ishan Kishan, Suryakumar Yadav show to beat New Zealand in Raipur (Olympics.com)

- Ishan Kishan 21-Ball Fifty vs New Zealand | IND vs NZ 2nd T20I 2026 (SportPreferred)

- Kishan and Suryakumar lay down marker in astonishing chase (ESPNcricinfo)

- ‘I asked myself…’: Kishan after his stunning 76 against NZ (NewsBytes)

- Optimal strategies in one-day cricket (Asia-Pacific Journal of Operational Research / World Scientific)

- Risk-taking, loss aversion, and performance feedback in professional sports (PMC / Frontiers)

- Cummins, and the ‘satisfying’ sound of silence (ESPNcricinfo)

- Cummins: An Aussie World Cup winning captain like no other (ESPN)

- Numbers Game: Is batting first such an advantage in Tests? (ESPNcricinfo)

- How Australia’s backstage orchestrators plotted India’s fall (Cricbuzz)

- Harmanpreet Kaur’s gut inspires call to let Shafali Verma bowl (ESPNcricinfo)

- Deepti, Shafali shine as India claim maiden World Cup title (ICC)

- Women’s World Cup 2025: Harmanpreet Kaur reveals ‘gut feeling’ led to Shafali Verma’s bowling decision in final (CricTracker)

- Recognition-Primed Decision Model (The Decision Lab)

- Dhoni, and Decision-Making – Learning from the Best (RevSportz)

- ‘Shafali’s bowling was the surprise factor, frustrating that we didn’t expect it’: SA captain Laura Wolvaardt (Times of India)