Traditional, as opposed to Environmental Economics, which is a later discipline, and will be a later post.

Economics is the science of human choices, because resources are limited, but human wants are unlimited. This is why every individual, business, and nation must constantly answer one question: how do we allocate our limited resources? We must decide how much goes to needs (essential for survival) and how much to wants (additional desires). This inquiry forms the cornerstone of economic thinking and shapes how modern finance, banking, and capital markets function.12

Because resources are scarce, and each resource can be put to multiple uses, when we choose one thing, we sacrifice something else. This sacrifice is called opportunity cost—the value of the best alternative forgone when making any choice. This is pervasive. An hour of time can be spent cooking, sleeping, watching cricket, gardening, socialising, reading, eating, working out, or any number of other activities. If one activity is chosen, the satisfaction from the others becomes the opportunity cost of that choice.12

Opportunity costs exist at every scale- for each person, for each group of persons (such as a family, or a nation, or our entire species), and for each resource, so that a rupee spent on something is also a rupee not spent on something else. At all times, we are making two choices: how to use our resources, and therefore, how not to use them.12

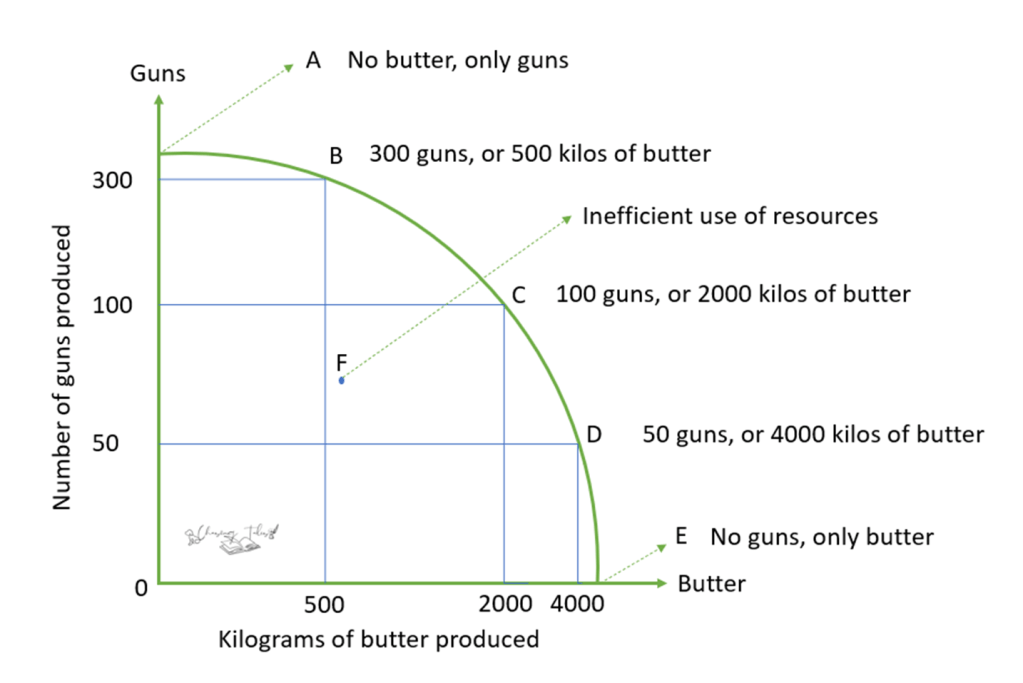

Imagine a hypothetical world where all resources can only be used to produce either ‘guns’ (military goods) or ‘butter’ (civilian goods). The more guns an economy produces, the fewer kilos of butter it can make, because resources are finite. This trade-off is represented by the Production Possibility Frontier (PPF), which shows all efficient combinations of the two goods. In an efficient economy, all resources must be used to produce either of these products, and when an economy chooses to produce less than it can, it is considered inefficient use of resources.34

Moving along the curve from more butter and fewer guns to more guns and less butter shows the opportunity cost: how many units of butter society must give up to produce one more unit of guns. That sacrifice is the opportunity cost of additional guns. Points outside the curve are unattainable with current resources and technology; they can only be reached if the economy grows or technology improves. Points inside it represent waste or unemployment, where some resources are idle or misallocated.34

Every economy must answer three fundamental questions:15

What should be produced?: This is about the mix of goods and services: food vs. defence, education vs. luxury items, public infrastructure vs. private consumption.

- In a market economy (capitalism), this question is largely answered by consumer demand and profit signals. If people are willing to pay more for smartphones than for pagers, firms produce smartphones.

- In a centrally planned economy, the government decides: for example, a state plan might say “this year we will produce X tonnes of steel and Y units of tractors.”

- In mixed economies (which is almost every modern country), markets decide most things, but governments step in for public goods and basic needs (roads, schools, defence, basic healthcare).

How should it be produced?: This relates to production methods, technology, and the combination of factors of production.

- A labour‑abundant country might choose labour‑intensive methods (for example, more workers, fewer machines) because labour is relatively cheap.

- A capital‑rich country might use highly mechanised production lines and automation.

- Environmental policies can also play a role: stricter pollution laws might push firms toward cleaner but more expensive technologies.

For whom should it be produced?: This is about distribution: who gets the goods and services once they are produced?

- In a pure market system, distribution is based largely on income and wealth. Those with higher incomes can command a larger share of output.

- Governments modify this market outcome through taxes, subsidies, and transfer payments. Different societies choose different degrees of redistribution depending on their values about equity, efficiency, and fairness.

As with all things in economics, this model too is based on multiple assumptions and is a drastically simplified explanation of the real world:

- Resources are fixed for the time period analysed

- Technology does not change

- The model shows only two goods for simplicity

- All resources are fully and efficiently employed

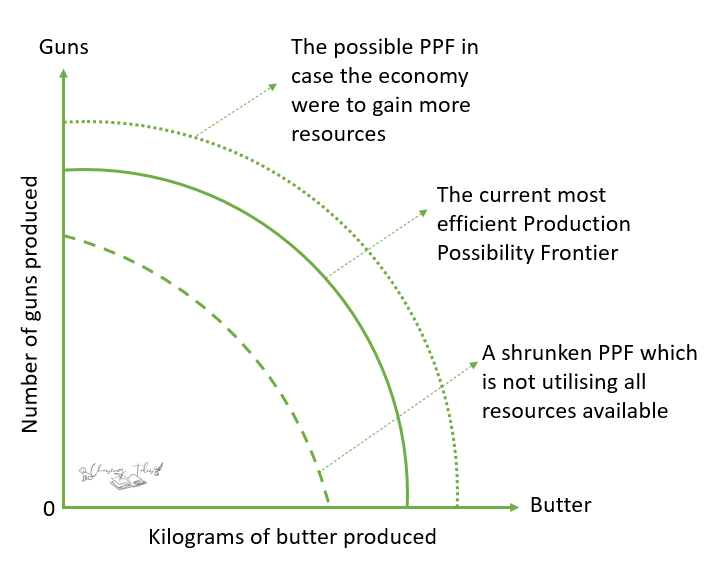

In the real world, economies grow over time as they acquire more resources (labour, capital) or develop better technology. This shifts the PPF outward, allowing production of more goods and services. Conversely, wars, natural disasters, or institutional collapse can shrink the PPF inward. Here’s a diagram depicting what happens to the PPF when such events occur:

Factors of Production67

There are currently four accepted factors of production in economics: Land, Labour, Capital, and Entrepreneurship.

- Land represents all natural resources, such as soil, water, minerals, forests, etc. The availability of these resources depends on a country’s location and directly influences which industries it can develop. A nation rich in oil has different economic opportunities than one with abundant forests or fertile farmland.

- Labour is the physical and mental effort people use to produce goods and services, including their skills, knowledge, and time. Education, training, the quantity of population, and workforce health directly impact a nation’s productive capacity.

- Capital are the physical and financial resources used in production. Physical capital includes machinery, buildings, tools, and equipment that help workers produce more efficiently. Financial capital refers to the money available for investment in developing new factories, technologies, or infrastructure. A country with abundant capital can invest heavily in production facilities and research, accelerating economic growth.

- Entrepreneurship is an intangible factor of production- the ability and willingness of individuals to take risks, innovate, and create new businesses. Entrepreneurs identify opportunities, combine the other factors of production in new ways, bearing risk and driving innovation and economic change.

These factors of production interact with each other to create an economy.

Microeconomics891011

Microeconomics focuses on individual decision-makers such as consumers, workers, and businesses, and how they allocate their limited resources.

The key to understanding microeconomic behavior is the concept of utility. “Utility” is the satisfaction, happiness, or value a person receives from consuming a good or service. Imagine an individual is very thirsty. They therefore drink water, and gain satisfaction from their thirst being quenched. At this point they can continue drinking water if they are still thirsty, and continue to gain satisfaction. However, the second cup of water will not be as pleasant as the first. The third is likely to be even less so. This is the principle of diminishing marginal utility (in economics, “marginal” means additional): each additional unit of consumption provides progressively less satisfaction than the previous one, until a point is reached when zero additional utility is gained from consuming water (or whatever). After this point, marginal utility turns negative: if they keep consuming more water, they’ll get sick.

Diminishing marginal utility explains everyday consumer behavior. At each decision point, consumers unconsciously ask: “Is the satisfaction I’ll get from this additional unit worth what I’m paying for it?” When marginal utility (the satisfaction from one more unit) exceeds the price, consumers buy. When it falls below the price, they stop. This individual decision-making across millions of consumers creates the market’s total demand and helps determine market prices.

Microeconomics also examines production decisions. Businesses constantly ask: Should we expand production? Should we hire more workers? Should we invest in new equipment? These decisions depend on costs and expected revenues, which means they depend on whether the marginal benefit of an additional unit of production exceeds the marginal cost. A business expands as long as producing one more unit adds more to revenue than it adds to cost. When marginal cost exceeds marginal revenue, expansion stops.

Macroeconomics12131415

Macroeconomics studies the economy as a whole. It asks large-scale questions: Why do some nations grow faster than others? What causes inflation? Why does unemployment rise during recessions? How can governments influence these aggregate outcomes?

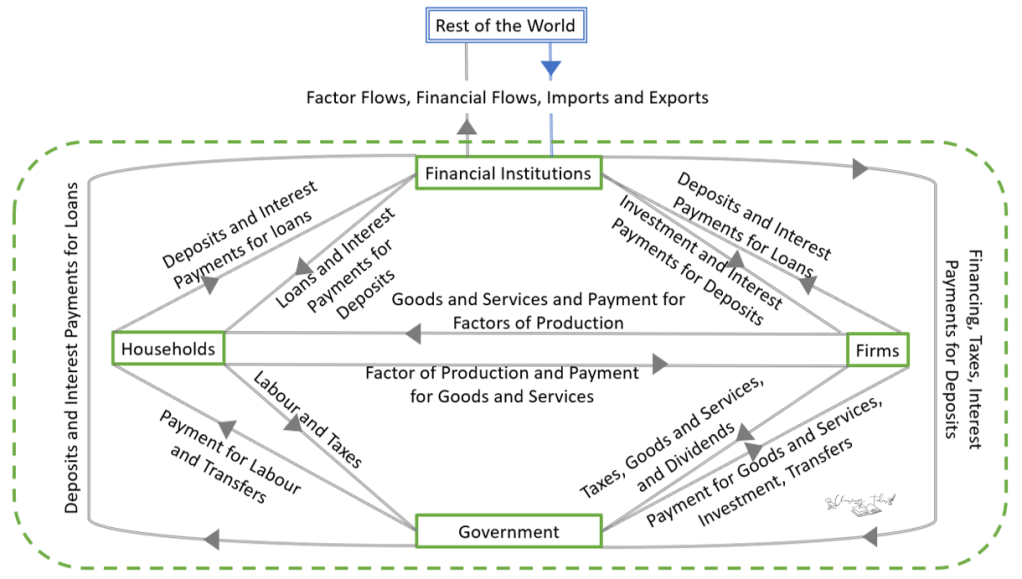

This diagram is called the ‘Circular Flow of Money’, and is a schematic representing the flow of money and goods and services in the economy.

Transfer payments are payments made by government (or sometimes private institutions) to individuals or businesses where no good or service is produced or exchanged in return. Unlike government purchases, which are payments for goods and services the government uses (like buying equipment or paying workers to build roads), transfer payments simply redistribute money from one group to another. The money is transferred from the government’s coffers (funded by taxes) to recipients who are then able to spend it into the economy. These payments are injections into household and firm budgets, and examples include unemployment benefits, lower or no cost medical facilities, food aid, business subsidies, etc.

There are five actors in this diagram: within an economy (inside the green dashed line), are Households, Firms, Financial Institutions, and Governments. Outside the economy being studied is the Rest of the World. Each country or economy in the world will have the same four actors according to this model.

- Households are individuals and families who own the factors of production (land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurship) and consume goods and services. They supply labour to firms and government, provide capital to financial markets through savings, and spend their income on consumption.

- Firms (businesses) are organisations that combine factors of production to create goods and services. They pay households for labour, borrow from financial institutions for investment, pay taxes to government, and trade with the rest of the world.

- Government (local, regional, and national) collects taxes, provides public goods and services, makes transfer payments, employs workers, and uses financial markets to manage surpluses and deficits. They inject money into the economy through purchases, wage payments, as well as transfers/ redistribution, and withdraw money through taxation.

- Financial Institutions (banks, investment firms, stock markets) accept savings from all sectors, provide loans and investment capital, facilitate all transactions in the economy, and connect domestic savers with both domestic and international borrowers.

- The Rest of the World represents all international economic activity—foreign countries, their consumers, their businesses, and their financial institutions. It connects domestic economies to global trade and international capital flows.

Since this is a schematic, the circular flow is based on simplifying assumptions, and is in any case a theoretical snapshot. It does not explicitly capture:

- Underemployment or unemployment

- Inequality and wealth concentration

- The detailed behaviour of governments and financial institutions

- Financial crises or speculative bubbles

The fundamental exchange of labour and capital flowing from households to firms, while goods and wages flow back represents the engine of the economy. One person’s spending becomes another’s income, creating a self-sustaining circular motion. When you buy groceries, you become income for the store’s employees, the farmer, the truck driver, and countless others in the supply chain. When they spend their wages, they create income for teachers, mechanics, doctors, and others.

This is why consumer spending matters so much for economic health. When households reduce consumption due to economic uncertainty, the immediate effect is lower revenue for firms. Firms respond by producing less, hiring fewer workers, and paying lower total wages, which means less income for households to spend, further reducing consumption. This negative feedback loop can trigger recessions. Conversely, when consumer confidence is high and households spend freely, firms expand, hire workers, pay higher wages, and the positive feedback loop accelerates growth.

Scaling individual choices

While individual consumers make utility-maximising choices and individual businesses make profit-maximising decisions, the aggregate of all these individual decisions creates macroeconomic outcomes.

When millions of consumers reduce their spending due to economic uncertainty, the aggregate effect is lower total consumption, reduced business revenues, lower investment, and slower economic growth. When governments lower taxes, households have more income to spend, which increases aggregate demand, prompting businesses to expand production and hire more workers. The multiplier effect amplifies these changes—an initial increase in spending creates a chain reaction of income and spending throughout the economy.

Interest rates illustrate this connection perfectly. A central bank raises interest rates to control inflation. Individually, this makes borrowing more expensive for a business considering a factory expansion. Collectively, as thousands of businesses postpone investment due to higher borrowing costs, aggregate investment falls, economic growth slows, and inflation moderates. The macroeconomic outcome emerges from millions of individual microeconomic decisions.

Individual choices by producers and consumers aggregate to determine what the entire economy produces and how. People choose what they want, whatever they think is best for them in the given moment keeping their personal constraints and preferences in mind, and this helps the entire economy choose what to produce, and how much, and using what methods.

How does this happen? The point at which the entire market settles is called an equilibrium. This is the point where the total demand in the economy matches the total supply.

Aggregate demand (AD) is the total amount of all goods and services that all buyers in an economy want to purchase at different price levels. It includes:

- Consumer spending (households buying groceries, clothes, services)

- Business investment (firms buying machinery, building factories)

- Government purchases (roads, schools, defence)

- Net exports (exports minus imports)

When the overall price level in the economy rises (inflation), people can afford less with their income, so the total quantity of goods and services demanded tends to fall. Conversely, when the price level falls, purchasing power increases, and aggregate demand rises.

Aggregate supply (AS) is the total amount of goods and services that all producers in an economy are willing to supply at different price levels.

In the short run, firms respond to higher prices by producing more (because higher prices mean higher profits). So when the price level rises, the quantity of goods and services supplied tends to increase. When prices fall, firms have less incentive to produce, so aggregate supply falls.

Over the long run, however, aggregate supply is determined by the productive capacity of the economy—the factors of production available (labour, capital, land, entrepreneurship) and the technology used. In this longer view, the price level does not affect how much the economy can fundamentally produce; that is determined by real resources and efficiency.

Macroeconomic equilibrium occurs when aggregate demand equals aggregate supply at a particular price level. At this equilibrium:

- The total amount consumers, businesses, and governments want to buy matches the total amount firms want to supply.

- There are no unintended accumulations of inventory (which would push prices down).

- There are no widespread shortages (which would push prices up).

- The economy settles at this price level and output level, unless something external changes.

When aggregate demand exceeds aggregate supply: The total spending in the economy is greater than the total output available. Imagine households and businesses want to buy more goods and services than firms can produce. This creates upward pressure on prices because:

- Firms see strong demand and can raise prices without losing customers.

- Businesses invest more to expand capacity.

- Workers may demand higher wages due to tight labour markets.

- This tends to push the price level upward (inflation).

If this imbalance persists, it can lead to “overheating” of the economy—rapid inflation as the economy bumps against its productive limits.

When aggregate supply exceeds aggregate demand: The total output produced is greater than what people want to buy. Firms end up with unsold inventory and spare capacity. This creates downward pressure on prices because:

- Firms lower prices to try to sell their excess stock.

- Businesses postpone investment and lay off workers due to weak demand.

- Workers have less bargaining power, and wage growth slows.

- This tends to push the price level downward (deflation or disinflation).

If this imbalance persists, it can lead to recession or stagnation, low growth, rising unemployment, and falling prices as the economy operates below its potential.

Over time, price changes and behaviour adjustments push the economy back toward equilibrium:

- If demand is too high and inventories are depleting, firms raise prices. Higher prices cool demand (people buy less because it is more expensive) and encourage supply (firms produce more because profit margins are higher). Gradually, demand and supply rebalance.

- If demand is too low and inventories build up, firms cut prices. Lower prices stimulate demand (people buy more because it is cheaper) and discourage supply (firms produce less because margins shrink). Again, they move toward balance.

In theory, this self-correcting mechanism should prevent persistent shortages or surpluses (this is what economists call “the invisible hand”, a metaphorical description of how the market corrects over‑ and under‑production, over‑ and under‑pricing, and similar imbalances). However, in the real world, these adjustments take time, and other factors (such as government policy, shocks, or expectations) can push the economy away from equilibrium before it settles.

| Aspect | Microeconomics | Macroeconomics |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Individual consumers, workers, firms | Entire economy, aggregate levels |

| Key questions | How do people allocate limited resources? Why do prices change? | Why do economies grow? What causes inflation and unemployment? |

| Key actors | Consumers, workers, businesses | Households, firms, governments, financial institutions, rest of world |

| Unit of analysis | Utility, profit, marginal decisions | Aggregate demand, aggregate supply, price levels, employment |

Modern applications1819

Traditional economic theory provides the foundation for understanding modern economies, which operate through sophisticated systems of banking, credit creation, and financial markets.

In traditional economies, money was often physical (coins and notes) and the money supply was limited by the amount of precious metal a nation possessed. Modern economies operate through a very different system where banks create money through lending: imagine a saver deposits INR 1,000 in a bank, the bank immediately lends most of that money to a business seeking a loan- let’s say INR 900. The business spends that INR 900, which ends up as deposits in another person’s bank account. That second bank then lends 90% of the INR 900, and the process repeats. They don’t lend the entire amount because they are required to keep a certain amount in reserve with the central bank. In India, this is called the Cash Reserve Ratio.20

The Cash Reserve Ratio is the percentage of a bank’s total deposits that must be held as liquid cash with the central bank, such as the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). It is a monetary policy tool used by the central bank to manage the money supply, control inflation, and ensure banks have enough liquidity to meet withdrawal demands (that is, the bank should have the money required for a normal amount of withdrawals). Banks cannot use this money for lending or investment, and they do not earn interest on it.

Suppose:

- The CRR is 10%.

- A person deposits INR 1,000 in a commercial bank.

The bank must keep INR 100 (10%) as reserves with the RBI, and can lend out INR 900. When that INR 900 is deposited by someone else:

- The second bank keeps 10% (INR 90) as reserves and lends out INR 810.

- The process repeats: each round, 10% is held as reserves, and 90% is lent out again.

In theory, the maximum amount of new deposits that can be created from the original INR 1,000 is determined by the money multiplier, which equals 1 divided by the reserve ratio (this is a simplified ‘maximum’ scenario. In practice, banks may be constrained by capital requirements, borrower demand, regulation, and risk management, so the actual expansion of money is usually smaller than the theoretical maximum).

If the reserve ratio (CRR) is 10% (or 0.10), then the money multiplier is 1 ÷ 0.10 = 10.

This means that the original deposit of INR 1,000 can theoretically support up to INR 10,000 in total deposits across the banking system (INR 1,000 × 10 = INR 10,000).

- Banks may hold extra reserves.

- People may hold some cash rather than depositing all their money.

This process is called credit creation or the money multiplier effect, where the original INR 1,000 deposit can eventually support INR 10,000 or more in total money supply in the economy. Banks don’t simply lend out existing money; they create “new” money through the lending process. This is why controlling the money supply is central to macroeconomic management.

In conclusion, traditional economic theory, built on scarcity, opportunity cost, and the interaction of supply and demand, gives us a language for understanding economic choices. It does not tell us what ought to be produced or who should benefit, but it clarifies the trade-offs and shows how millions of individual decisions aggregate into the performance of entire economies.

Sources

- Lesson summary: Scarcity, choice, and opportunity costs – Khan Academy

- Scarcity and Opportunity Cost – LibreTexts, Econ 101: Economics of Public Issues

- Production Possibility Frontier (PPF): Purpose and Use – Investopedia

- Complete Guide to the Production Possibilities Curve – ReviewEcon

- Scarcity, Choice and Opportunity Cost – Physics & Maths Tutor (A‑level notes, PDF)

- Factors of Production – Wall Street Prep

- Factors of Production: Land, Labor, Capital and Entrepreneurship – Corporate Finance Institute

- Microeconomics – Investopedia

- Microeconomics course home – Khan Academy

- 14.01SC Principles of Microeconomics – MIT OpenCourseWare

- Microeconomics – Encyclopedia Britannica

- Macroeconomics – Investopedia

- Macroeconomics course home – Khan Academy

- What is macroeconomics? – Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

- Macroeconomic and Fiscal Policy – World Bank (Economic Policy topic)

- The Circular Flow of Income – Saylor “Economics: Theory Through Applications”

- Circular Flow Model: Definition & Examples – Study.com

- Multiplier Effect: How Fractional Reserve Banking Creates Money – Management Study Guide

- Banking and the Expansion of the Money Supply – Fiveable (AP Macroeconomics)

- Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR): Meaning, Objectives & Current CRR – ClearTax

2 thoughts on “A note on traditional economics”